It’s been a minute since I waxed leonine about popular media on this blog, and the discussion I’ve been seeing online this week about the latest Netflix limited series put me in a Mood™.

There’s an old expression you may have heard: “To the hammer, everything’s a nail.”

About a thousand years ago, I saw the film Excalibur with a friend who was a history buff (and, ultimately, a history teacher). He said it was a bad film because of certain historical inaccuracies. I corrected him politely: “As a history buff, you didn’t like the film because of the ahistorical elements. If that sounds pedantic, it’s really not: preference and quality aren’t the same thing. The reception of art is almost fully subjective, but art itself is a field, same as any.”

To his credit, he conceded the point, but only because he understood its logic in the abstract: As someone who didn’t work in film and never studied it, he had no idea what the form was about.

Excalibur is easily the best Arthurian feature film of all time, and one of my top 10 favorite films of any kind or genre. As a piece of film art, Excalibur is easily defensible as a masterpiece.

Along the same lines, I saw the films Pi and Good Will Hunting with a math guy (who ultimately became a math teacher). He said the math was poop in both cases, and therefore, that both films were bad films. Neither film was actually about math, but as a math guy, my friend was a pretty long jog from being in a place where he could apprehend the substance of that argument.

Pi and Good Will Hunting were both, famously, award-winners. They earned the accolades they won as a recognition for dramatic filmmaking art, not for any documentary effort of any kind.

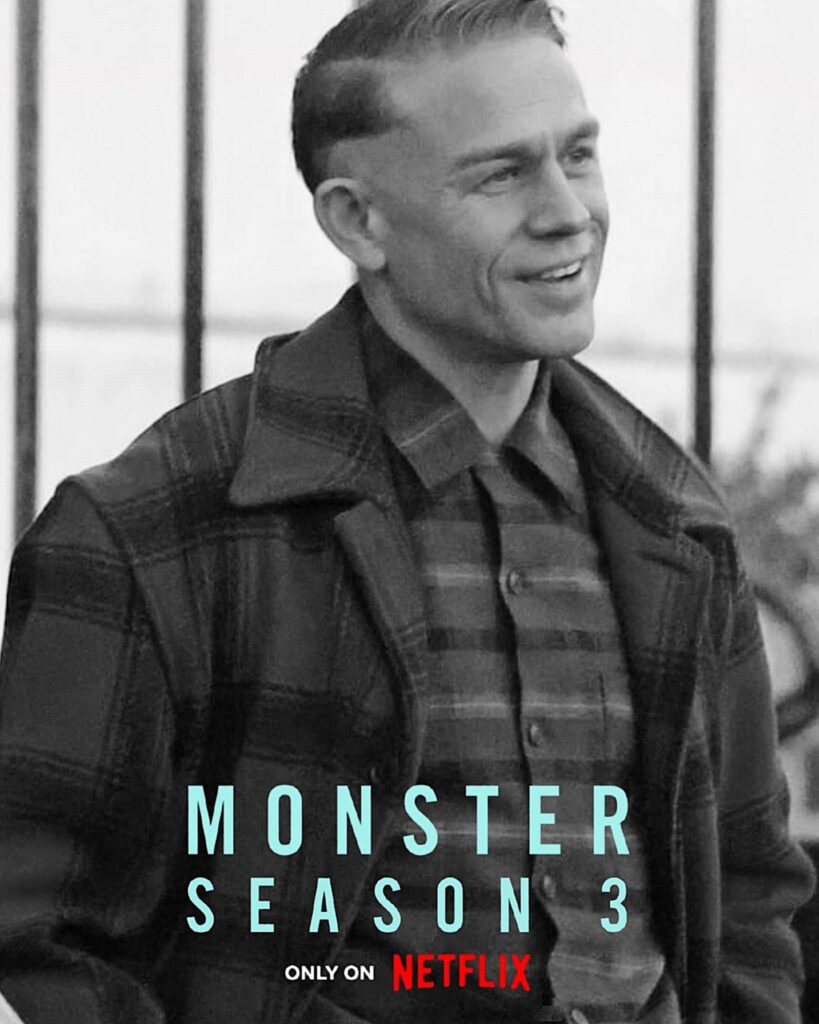

This week, I’ve seen more than a comfortable number of people taking all kinds of piss out of Ryan Murphy’s latest piece of dark art. In this case, it’s season three in his Monster series on Netflix, a continuation of what he began with one-off seasons about Jeffrey Dahmer and the Menendez brothers (and will continue with one about Lizzie Borden, if scuttlebutt holds true).

Fair Disclosure: Ryan Murphy has disappointed me in the past, too, folks, and plenty. I’m no RM fanboy. But… the more you watch him, especially in the context of his being a mass-media artist who keeps up with an ever-changing culture, the more you understand what he’s doing.

Frankly, I now know more about the real-world Ed Gein than I ever really wanted to know. There are something like 40 documentary films and series about the historical Ed. (I believe the taxonomic term for that quantity of offerings is a “shitload”, but I’d have to double-check.)

Plus, of course, all the pop media touchstones that Ed Gein and his story went on to inspire, which is one of the very things Murphy’s new series is expressly critiquing.

Ryan Murphy’s piece of art is, well, a piece of art. It’s not the 41st in that line of documentary efforts. It’s a scripted fiction, saying what its creator/showrunner wants to say about its subject matter, that happens to be inspired by real-life events, featuring people who really did exist (or, in the case of Gein’s girlfriend, might have existed, but I digress).

If you walk out of a three-hour period costume drama, and the person you sat next to in the theater for three hours says, “That movie stunk because it hardly made me laugh at all”, you’d be within your rights to point out that the three-hour costume drama about being miserable in whatever era never promised to make you laugh. At all, let alone throughout the experience.

Holding that piece of art to that standard is nonsense. Not just missing the point, but wrong, in the way logical and rhetorical fallacies are wrong. It’s bad assessment, meaningless as criticism, and more often than not, a bit embarrassing on the part of the person engaging in the behavior.

As it happens, scripted media has been trending in the direction of blurring these lines more than ever. One could say the trend really began 28 years ago, with Fargo, which many viewers assumed was based on a true story because, well, the film literally talks about it being a true story in the opening frames. Problem is, that little disclaimer was itself a part of the art.

Fargo is not based on a true story. The Coen brothers made it all up.

Last year, a thriller called Strange Darling dropped, and it immediately sent people scurrying to the Internet to find out which real-life female serial killer inspired the film, since the film presents her story as if it’s real. Problem is, she is not real. J.T. Mollner made her up.

The Conjuring universe, which is arguably the most successful horror film franchise of the century so far, revolves entirely around telling overtly (absurdly, even) supernatural stories that are inspired by certain real-life figures and situations. Historicity is absolutely not the point.

This is an actual ongoing trend in Hollywood, and Ryan Murphy’s Ed Gein-inspired series falls into place perfectly alongside those other offerings. People getting offended because Ryan Murphy did what Ryan Murphy does, are the ones guilty of failure here: a failure of expectation.

To those people, I would say the same thing I said to my history buff friend, and my math guy friend, and numerous others, every time they allowed their misapprehension of how best to take art in essentially defecate on their own ability to get any joy or meaning out of art:

Let the factuality go, and try to appreciate what the art is saying and doing with the material.